Can a Date Decide an Election?

Mayor Booker benefited from certain electoral biases when he coasted to victory on Tuesday.

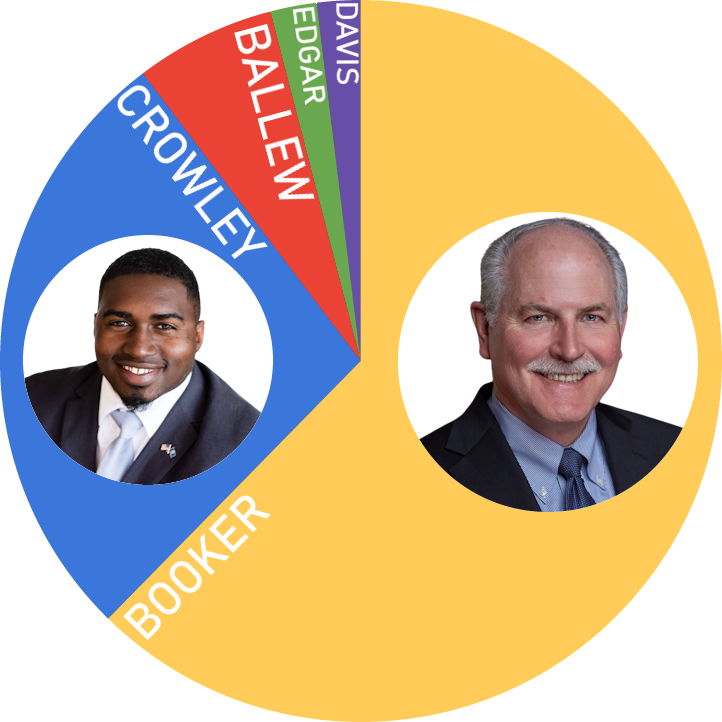

Last week, Mayor Booker prevailed against a crowded field of candidates in the 2024 Lawton mayoral election. Winning more than twice the number of votes as his closest rival, Mayor Booker is now set to begin his third term. Having proven himself an enduring politician in the City of Lawton after fighting off a recall attempt in the height of the pandemic, Mayor Booker focused his last campaign on defending his record against criticism of the Westwin project and advocating for Lawton’s new capital investment project.

However, why Mayor Booker succeeded in his most recent campaign can’t be boiled down to simple issue polling. As with many political events, this election was less about the players and more about the game. Politics is not a soap opera drama, but a system, structured around rules that preference certain outcomes. In this case, Mayor Booker benefited from biases that affect off-cycle elections in Lawton, which helped to carry him to his overwhelming victory.

It is well-known among the general public that those who are already in office are more likely to stay in office, and political scientists have long recognized this fact in literature. In a 2018 study of over a thousand mayoral elections from 1950 to 2014, a political scientist at Harvard found that incumbents were twenty-five percentage points more likely to win a given election than their challengers. Lawton’s most recent election, in this sense, was no exception.

However, in another sense, Lawton’s election was strange. In the same study, the Harvard researcher found that, in off-cycle elections like ours, voters are more likely to throw incumbents out of office. In general, during a November election, voters will be thinking more about the big ticket races for the Presidency, the Senate, and the House which means they will be less likely to think about who their mayor should be. In an off-cycle election, this dynamic is reversed: the only voters who show up are those who have strong opinions about local politics, and these informed voters are more likely to vote new candidates into office.

I argue here that Mayor Booker’s whopping success at the polls is evidence that the opposite trend might exist in Lawton. Mayor Booker did not win despite the date of the election. Arguably, he partly won because of it. Unlike most elections where low turnout favors the removal of incumbents, in this election, the sort of voters who were most inclined to support Mayor Booker were the sort of high-turnout voters most likely to vote in an off-cycle election.

In a 2019 study, political scientists at the University of Boston found that Black and Hispanic voters were far less likely to turn out in off-cycle elections than their white counterparts. In three of the four major cities analyzed, Black voters were 6-10% less likely to vote in those elections, and Hispanics were 10-23% less likely to vote in all four cities.1 In another study, the authors described how off-cycle elections “reduce turnout among marginal voters.” As they put it, “the electorate in off-cycle races is older, wealthier, and whiter” than the median voter.

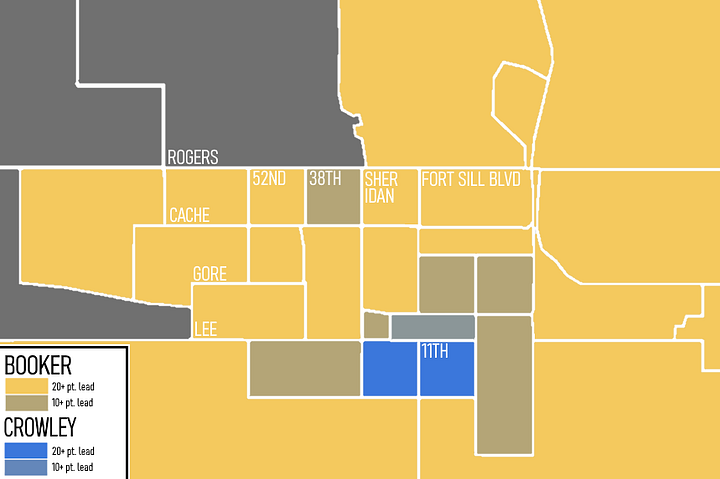

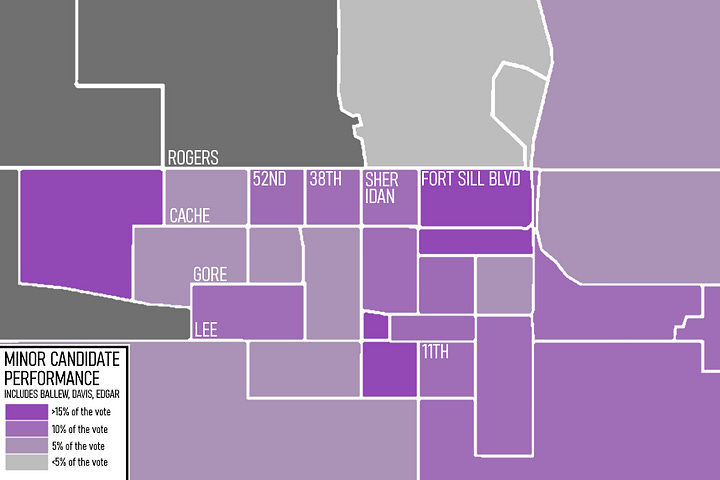

All this matters because, in Lawton’s mayoral election, supporters of Mr. Jacobi Crowley, the primary opposition candidate, were disproportionately Black. Mr. Crowley won two precincts in the election, both of which are majority Black, and he performed well in the disproportionately Black, low-income neighborhoods of south-central Lawton. Other, less significant candidates also performed well in the poorer, more diverse neighborhoods of central Lawton relative to the rest of the city. Meanwhile, Mayor Booker’s base of support,was strongest in Lawton’s primarily white, middle-class suburbs where he routinely trounced opposition candidates by up to forty points.

Mayor Booker’s supporters turned out in a way that the potential supporters of other candidates did not. His older, wealthier, and whiter supporters showed up in droves for a strangely-timed election, while other candidates’ would-be voters stayed home.

Of course, this is not the only reason that Mayor Booker won. The opposition to Mayor Booker was fragmented around multiple, ideologically diverse candidates, meaning each candidate may have chipped away at the others’ vote share. Non-partisan elections like ours also favor candidates who can accumulate a large “personal vote” from voters who primarily support a candidate for their reputation or their relationships in the community. Incumbent candidates like Mayor Booker often win the personal vote precisely because they have been mayor, and they have the personal and political connections that come with the mayoralty.

Regardless, in future elections, it would do Lawton’s mayoral candidates good to remember when the election is being held. Lawton’s low-turnout, August elections lend themselves to older, whiter, and more affluent voters. If a candidate wishes to win the election, they either need to appeal to high-turnout voters like that or, they need to make exceptional efforts to organize Lawton’s low-turnout voters and get them to the polls.

The study reported an exception among Black voters in Atlanta. Black voters in Atlanta were more likely to vote in off-cycle elections than their white counterparts. This phenomenon could be reasonably attributed to Georgia’s vibrant network of grassroots groups that work to mobilize Democratic-leaning voters, especially Black voters.