Our Amoral Elite

In America, legislators are scarcely permitted to vote their conscience. Perhaps we should let them.

In a few months, our Anglophone cousins across the Atlantic are going to vote on the legality of assisted dying. If the bill passes, the United Kingdom would permit elderly individuals suffering from painful, terminal illness to end their lives with the assistance of a doctor. This issue is deeply controversial. Numerous columnists and politicians have written editorials, making impassioned pleas from across the political spectrum. Conservatives, liberals, and socialists alike are arguing for and against reform.

The matter of assisted dying is so important– yet so divisive and ethically complex– that the leaders of the United Kingdom’s political parties have chosen to leave this issue to each individual legislator. While each party’s leader has expressed his position on the matter, they all agree that it is not for them to decide.1 They argue that for an issue this personal, it only makes sense that members of parliament should be allowed to vote for themselves, to exercise their own moral discretion in casting their ballot. Assisted dying is a matter of life and death. It is an issue that is weighty enough to transcend mere partisan politics.

In the United Kingdom, such votes of conscience are rare, but common enough. Previously, members have been allowed to vote their conscience on abortion, homosexuality, and the death penalty.2 While some votes have ultimately fallen largely on party lines, legislators were permitted to express their own opinions. Each vote has represented a ceasefire. In an act of incredible humility, the head honchos of each party set down their whips and acknowledged that some issues are bigger, more fundamental, and more personal than politics.

In the United States, we have similar arrangements from time to time, but not consistently and not as a concerted, multi partisan truce. The most significant vote of conscience in recent memory was in 2020, when Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell declared that Republican senators were free to vote their conscience on Donald Trump’s conviction after impeachment. Democrats were not similarly liberated, though perhaps, this was for the best. While McConnell had expressed mixed opinions on whether Trump should be barred from holding office, his party didn’t buy his vision for a free vote. Of the seven Republican senators who voted for their conscience and against their party, three didn’t run for re-election or resigned before they could, three were well-established political mavericks, and one was censured by his state party for his vote.3 This “free” vote was a farcical declaration, an unmarked poison pill.

Representative Liz Cheney offers a particularly harrowing description of what it means to vote one's conscience in modern American politics. In her memoir, she describes how dozens of Republicans, from the then-minority leader Kevin McCarthy to right-wing rabble-rouser Chip Roy, were in favor of impeachment on moral grounds, but neglected to vote for it due to practical considerations.4 They knew that voting for impeachment could put their careers, or even their lives, on the line. Following his vote, Representative Peter Meijer received death threats, and he began wearing body armor in his day-to-day life for fear of an attack: "I came out here to serve my country," he said, “regardless of the cost or of the consequences to me personally or politically.” Representative Meijer soon lost his re-election campaign to a Trump-endorsed challenger, as did Representative Cheney.

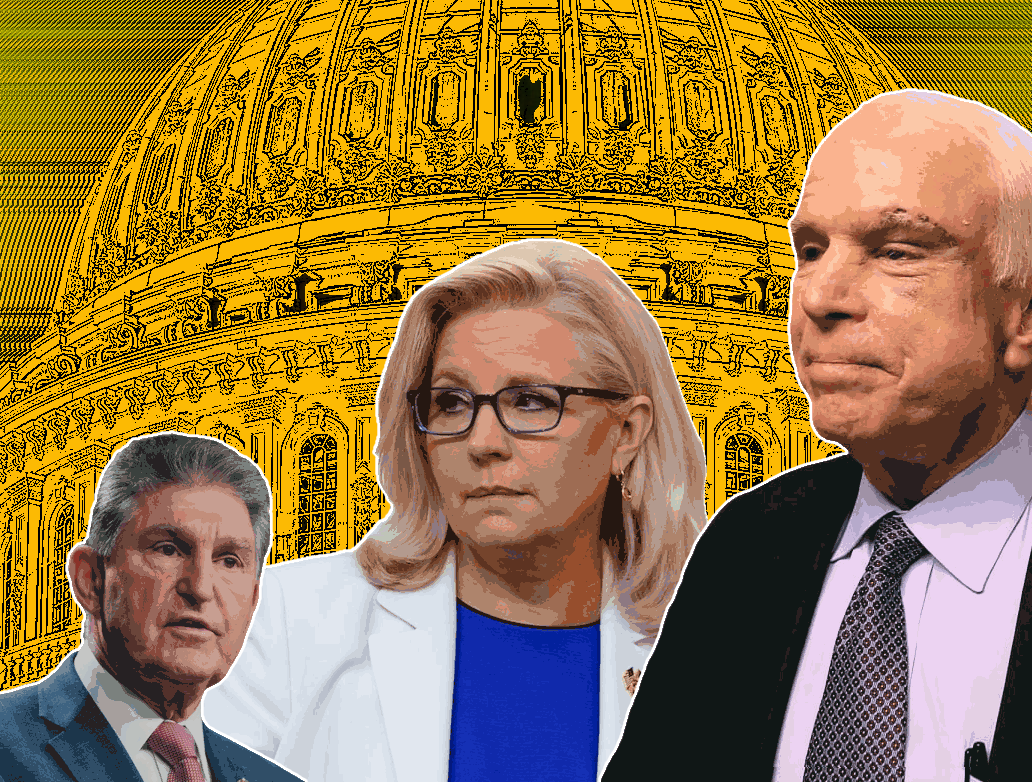

There are numerous systemic reasons why politicians are not often permitted to vote conscience in the United States. In the United Kingdom, political parties are much stronger than they are here. When party elites decide that a vote should be left to conscience, it is. America’s weaker political parties also give leeway for individual mavericks to rebel on an ad hoc basis while retaining good-standing. Senator Manchin’s refusal to toe the line for Biden’s Build Back Better Act comes to mind, as does Senator John McCain’s famous “no” vote on Trump’s attempt to repeal Obamacare. However, these incidents are sporadic and often as cynical as their party-line votes, and most legislators lack the individual political support necessary to overcome partisan pressures anyhow.5

The United States also has a much stronger judicial branch while the United Kingdom defers to a principle of “parliamentary supremacy”. In my time working at the Oklahoma House of Representatives, I heard representatives discuss how, although they personally opposed many bills they voted in favor of, they trusted that the Oklahoma supreme court would strike them down if they transgressed ethical boundaries. Because our system assumes that men are not angels, it does not demand that they act as such. Our politicians often act with regard to personal political ambition alone.

Regardless of why their government has formal conscience votes and ours does not, I lament. I like the idea that a politician would be so humble as to acknowledge that an issue is too much for them to bear. In an era where populists pretend complicated issues are simple, where politicians cram real moral dilemmas into the clothing of absolute moral rights, I can appreciate the simple virtue of saying “I don’t know.” By pretending that fluid moral questions are solid and that those who disagree are fringe fanatics, we deny ourselves the virtue of debate which gives way to human reason, the first prerequisite of a democratic system. Politics should not be and cannot be an all-encompassing, life-and-death discussion. There are virtues that exist beyond this game for which we are only accountable to ourselves and (perhaps) our Creator.

In coming years, as America hopefully begins to depolarize and “turn down the temperature” in our discourse, we should re-evaluate what we expect from our politicians on moral questions. As voters, we should be open to politicians having strong moral principles even if those principles may at times differ from our own. We should punish parties, not for being ideologically incoherent, but for being morally intolerant. We should reward politicians for being honest and not concealing their fundamental beliefs for the sake of political expediency. At times, we should permit our politicians to vote their conscience.

To see each party’s position on the subject, click here for left-leaning Labour, the centrist Liberal Democrats, and the right-leaning Conservatives.

This source is obsolete, but comprehensive. From my research on individual pieces of legislation, the systems it describes have largely remained in-tact.

Not running/resigned: Burr (NC), Sasse (NE), Toomey (PA)

Maverick reputation: Collins (ME), Murkowski (AK), Romney (UT)

Censured: Cassidy (LA)

Liz Cheney, Oath and Honor: A Memoir and a Warning (Hachette UK, 2023), Chapter 18.

Senator Kirsten Sinema (AZ) is a good example here.