When Richard Nixon Was a Diversity Hire

While the vice presidency has changed, its moral purpose has not.

Yesterday, JD Vance and Tim Walz stood off against each other in this year’s sole vice presidential debate. It began with a brief statement from the moderators, describing the tumultuous state of the world and the country before asking Tim Walz about Israel’s recent attack on Lebanon. Tim Walz gave a policy-oriented response where he yammered a bit about the horridness of Hamas and the importance of Israel before clunkily shifting into a well-worn criticism of Donald Trump: that he doesn’t care about America’s allies and that he lacks the temperament to be president. He said Harris would protect American allies and American interests. Simple as.

The moderators then asked Vance for his response and his position on the conflict. He assured the moderators that he would get around to answering the question, and then he turned to the camera. He thanked the American people for caring enough to tune into the debate, and he began to talk about himself and his background.

In the moderators’ introduction to the debate, they described a solemn, important occasion where two powerful men would discuss their ideas for the future of the country and the world. The story of JD Vance, his humble origins, and his mom’s opioid addiction weren’t on the roster tonight, but these subjects were nonetheless crucial. Not only was it crucial for JD Vance to humanize himself to the voting public, but it placed JD Vance in a long line of vice presidents who were selected for the office not merely on the strength of their merits, but the uniqueness of their background. Objectively, the vice president has always been a diversity position.

A vice president’s diversity, defined here as the various traits that distinguish them from the president, has always been an important factor in their selection. The framers of our Constitution designed the office of the vice presidency in order to heighten the representative power of the executive branch, and the way in which political parties have used the office throughout history is a testament to America’s changing conceptions of diversity.

1804 - 1960: The Twelfth Amendment and WASP Dominance

The Twelfth Amendment of the Constitution, passed in 1804, created the vice presidency as we understand it today. While there were vice presidents before the Twelfth Amendment, the office functioned differently. As the famous Broadway play Hamilton describes, the vice president was the candidate who came second in the presidential race. While the second-most-voted presidential candidate was theoretically the second-most-qualified person to be president and the most qualified person to take over on the occasion of the president’s death, in practice, the rise of political parties meant that this system created some uncomfortable arrangements. The Federalist Aaron Burr shot and killed Alexander Hamilton while serving as Vice president in the administration of Thomas Jefferson, a Democratic-Republican.

Enter the Twelfth Amendment. Some legal scholars have argued that the Twelfth Amendment is among the most transformative, underrated amendments to the United States Constitution. It virtually guaranteed that the vice president would be subordinate to the president, unable to build political coalitions outside their own party or thwart the president’s agenda from the inside, as Jefferson and Burr did to their respective presidents. Another important problem that the Twelfth Amendment solved was that of the “Favorite Son” executive branch. The framers of the Constitution feared that the electors of the electoral college might favor presidential candidates from their own state, which would undermine the representativeness of the executive branch. The Twelfth Amendment solved this problem by explicitly prohibiting electors from casting their ballot for two candidates from their state.

In effect, the Twelfth Amendment mandated that a presidential ticket should represent regional diversity. If two candidates from the same state ran on the same ticket, then one of those candidates would be ineligible to receive votes from their home state. This amendment gave rise to what we would later refer to as “ticket balancing”, or ensuring that the vice president would complement the president’s traits and bring something new to the ticket. In other words, party leaders would select the vice president based on how he or she could bring diversity to the ticket.

While nearly all the vice presidents of this era were white Protestants of English descent, they nonetheless represented diversity as American elites in that time conceived of it.1 In the 19th century, there were only five cases in which the president and vice president were not from different regions of the country. Political elites viewed the selection of the vice president as a way to unite their own political parties by appealing to their diverse regional factions and to draw out voters in key states.2 Richard Nixon was the last vice president to serve in this first era, and he was a true diversity hire by the standards of the time. While Dwight D. Eisenhower was an old, moderate outsider candidate from the east coast, Richard Nixon was a young, conservative with establishment credentials from California. While they were both white, Anglo-Saxon Protestants, they had different philosophies from different coasts in different generations.

1960 - 2000: Inclusive Politics and Changing Diversity

As the vice presidency has evolved over the course of the previous two centuries, it has grown to accommodate our nation’s ever-growing recognition of its diversity. 1960 marked a watershed moment in the history of the vice presidency. When John Kennedy selected Lyndon Johnson as his vice president, it was the first time that a Catholic and a Protestant would serve together on the same ticket. Kennedy symbolized of the rising status of so-called “white ethnics”— those white Americans who don’t trace their ancestry to North America’s historical English elite, but to relatively recent migrants from Ireland, southern europe, and eastern europe. Johnson’s selection was an olive branch to the Anglo-Saxon established order.

With the feminist and civil rights movements of the 1960s and 70s, American society began an unrelenting move towards a broader view of diversity. From 1960 to 1976, half of all presidential tickets included both a Catholic and a Protestant, and three included a white ethnic candidate. In 1984, Walter Mondale broke multiple precedents when he selected an Italian-American woman as his vice presidential nominee, and George H.W Bush kicked off a tradition of appointing younger people for the second slot when he selected Dan Quayle in 1988. In recent years, multiple vice presidential candidates have been elevated on account of their unique personal stories, including the working-class hillbilly JD Vance and Coach Tim Walz. Of course, no discussion of the increasing diversity of the American vice presidency would be complete without mentioning the 2008 Obama-Biden ticket, the first presidential ticket to feature an African-American.

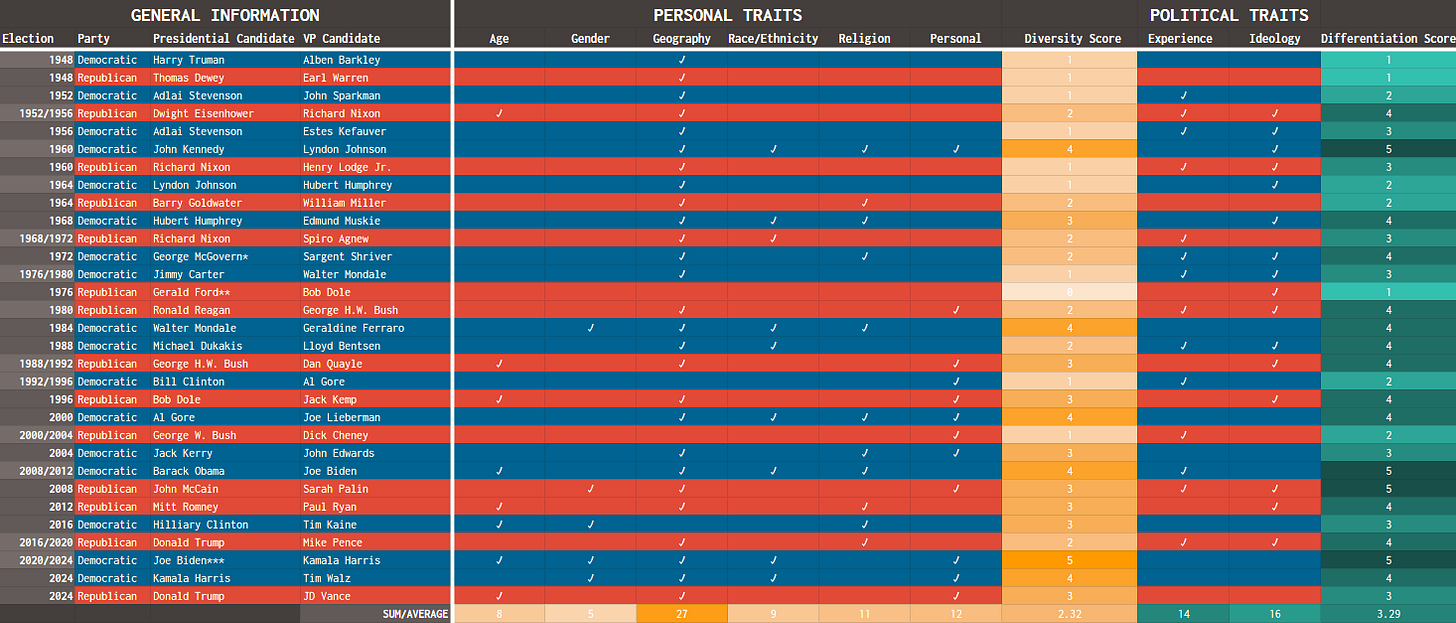

The chart below documents the rapid evolution of the vice presidency and the rapid evolution in what Americans regard as diversity. With two exceptions, every vice president of the past twenty years has had at least three personal traits distinguishing them from the president, whether that trait is their age, gender, race, ethnicity, religion, geography, or background.

As seen on the chart, the expanded diversity of the vice presidency hasn’t merely applied to their personal traits, but their political traits too. Presidents have grown more likely to appoint a vice president who is not only from a different region of the country but also from a different wing of their political party. Moderates have begun to share the presidential ticket with ideologues, and radicals have grown to appreciate the virtues of a more measured running mate. While Barry Goldwater (1964) and Bill Clinton (1992) used their vice presidential nominees as an opportunity to demonstrate their commitment to their principles, Michael Dukakis (1988) and Mitt Romney (2012) used their selection as an olive branch to other factions within their party.

Furthermore, as political outsiders have grown increasingly potent within federal politics, the vice president has also provided tickets with diversity in experience. When Georgia governor Jimmy Carter ran for president in 1980, he didn’t opt for a fellow peanut farmer, but for Walter Mondale, a veritable creature of Washington with years of experience in the Senate. The opposite goes for John McCain. A longtime fixture of Washington politics, McCain (2008) opted for an obscure, Alaskan governor as his VP pick to appeal to those who lamented the status quo.

2000 - Today: The Modern Vice President

Today, distinct difference exist between the Republican and Democratic Parties in how they select their vice presidents and think about diversity. While Democrats often use their vice presidential pick to appeal to various social groups, Republicans usually pick someone who brings different career qualifications and ideological diversity to the ticket. The 2008 election is a good case study in this regard. While the maverick Senator John McCain added the outsider conservative Sarah Palin to his ticket, the young, Black Protestant Barack Obama added the old, Irish Catholic Joe Biden to his. In some ways, these differences in vice presidential selection reflect increasing partisan polarization and the widening philosophical gaps between our political parties. While Democrats appeal to diversity of gender, race, and religion, Republicans are more likely to think of diversity as different ideas and life experiences.

Our executive branch, more than ever before, represents the diversity of the American people. More than any other point in American history, the average American is likely to see themselves reflected somewhere on the presidential ticket. From the founding of the United States as a mere collection of united states, we have evolved into a more perfect union, elevating working-class people, racial minorities, immigrants, and women to the dignity of citizenship. When our country was founded, neither Kamala Harris, Tim Walz, nor JD Vance would have been considered valid candidates for vice president on account of their ancestry and their modest upbringing. Today, they are.

While our nation has changed, our values have not, and the vice presidency reflects our attempts to live up to our high virtues. It reflects the ways in which our social order and our politics has become more inclusive. While both parties have grown to think about diversity in different ways, our institutions have nonetheless grown more representative across every area of society. Once lamented as a powerless office, lacking in prestige and purpose, the modern vice president serves as the president's chief advisor and partner in administration, providing an essential asset to the White House: perspective.

One glaring exception: Vice President Charles Curtis, elected in 1928, was Native American.

Jody C. Baumgartner, The American Vice Presidency Reconsidered, 2006, https://doi.org/10.5040/9798400612404, 19. For a more exhaustive documentation of sources, click here.